What is Logic

I studied logic. Now I write software for a living. This confuses some people. What is logic? How is it related to computers?

This is how I understand it.

Logic

Logic is the study of inference: of drawing conclusions, or extracting information out of the information we already have. Some examples of inferences:

- If someone says he lives in Boston, then I can infer that he lives in Massachusetts

- If I know I’m driving 60 mph, and I have 30 miles left to go, I can infer that I still have a half hour left to drive

- If I know that Smith is a human, and I know all humans are mortal, then I can infer that Smith is mortal

- If I know that Jones hurts people for fun, and that only bad people hurt people for fun, then I can infer that Jones is a bad person

And so on. This is the kind of thing that logic studies.

One of the things that logic tries to do is to provide rules for drawing inferences:

- rules that eliminate the possibility of drawing false conclusions from true premises

- rules that objectively settle disputes about what conclusions can be drawn

- rules that de-psychologize the process of inference entirely – i.e. that remove our reliance on what we “feel” the conclusions of a sentence are

Computation theory was born out of an attempt to use these rules to settle a dispute in mathematics.

Arithmetic

Arithmetic is the portion of mathematics that people tend to learn how to do

early in school. It covers addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and

the like. When you add 5 to 7 to get 12, you are doing arithmetic.

We tend to think of arithmetic as a kind of symbolic game. We move symbols around, write new ones, substitute this symbol for that, carry a 1, cross out a 3, etc., according to some very specific rules. At the very least, this is how we are taught arithmetic. If we follow the rules, we succeed. And we seldom, if ever, think about anything else. Arithmetic is mere symbol manipulation.

Frege’s Program

Gottlob Frege, a German logician and mathematician, wanted to prove that something like this commonplace view about arithmetic was correct. He believed that one could infer all of the true equations simply by applying some very specific rules to some very specific symbols. The symbols were those of set theory. And the rules were those of logic.

The book that resulted from Frege’s attempts to develop a logic strong enough to infer arithmetic from set theory was the Begriffsschrift, published in 1879. Frege then published Die Grundlagen der Arithmetik (The Foundations of Arithmetic) in 1884 to complete his project. There, he attempted to define the major terms of arithmetic using only set theory and logic:

[T]he natural numbers 0, 1, 2, 3, etc., considered as sets [. . . can be] defined in purely logical fashion, namely, for 0 the set of things not identical with themselves, for 1 the set whose sole member is the number 0, for 2 the set whose members are the numbers 0 and 1, for 3 the set whose members are the numbers 0, 1, and 2, and so forth. (Kneale and Kneale, The Development of Logic, pp467-468)

By the beginning of the 20th century, Frege thought he’d succeeded:

I hope I may claim in the present work to have made it probable that the laws of arithmetic are analytic judgements and are consequently a priori. Arithmetic thus becomes simply a development of logic, and every proposition of arithmetic a law of logic, albeit a derivative one. (Grundlagen, §88)

But a young logician out of Cambridge named Bertrand Russell wrote to him in the summer of 1902:

[date: 16 June 1902] Dear colleague, For a year and a half I have been acquainted with your Foundations of Arithmetic, but it is only now that I have been able to find the time for the thorough study I intended to make of your work. I find myself in complete agreement with you in all essentials[.] [. . .] There is just one point where I have encountered a difficulty. You state that a function, too, can act as the indeterminate element. This I formerly believed, but now this view seems doubtful to me because of the following contradiction. Let w be the predicate: to be a predicate that cannot be predicated of itself. Can w be predicated of itself? From each answer its opposite follows. [. . .] Very respectfully yours, Bertrand Russell.

Russell discovered a contradiction – today known as Russell’s Paradox – at the heart of Frege’s system. Frege replied to Russell’s letter:

[date: 22 June 1902] Dear colleague, My thanks for your interesting letter of 16 June. [. . .] Your discovery of the contradiction caused me the greatest surprise and, I would almost say, consternation, since it has shaken the basis on which I intended to build arithmetic. [. . .] It is all the more serious since, with the loss of my Rule V, not only the foundations of my arithmetic, but also the sole possible foundations of arithmetic, seem to vanish. [. . .] In any case your discovery is very remarkable and will perhaps result in a great advance in logic, unwelcome as it may seem at first glance. [. . .] Very respectfully yours, G. Frege.

Frege was devastated by Russell’s discovery. Nevertheless, the focus in mathematics and logic remained on Frege’s project.

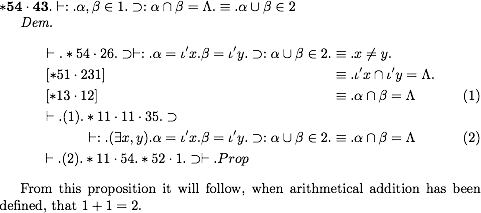

To that end, Russell and Alfred North

Whitehead published the

monumental Principia Mathematica in

1910 – another attempt to derive arithmetic from set theory. Here, after about

400 pages, they finally prove that 1 + 1 = 2:

With time, however, mathematicians grew increasingly worried that what happened to Frege would happen again: that there were contradictions hiding in these increasingly complex logical systems. A subtle shift in focus began to take place: from proving this or that portion of mathematics, to proving that one’s proof was consistent. The influential German mathematician, David Hilbert, once claimed:

The chief requirement of the theory of axioms must go farther [than merely avoiding known paradoxes. It must show that] contradictions based on the underlying axiom-system are absolutely impossible. (1918, “Axiomatic Thought”)

Hilbert – who had done for geometry what Russell and Whitehead did for arithmetic – even went so far as to claim that the second most important outstanding problem in mathematics was whether there was any consistent set of rules for arithmetic.

It’s hard to overstate the influence of Frege’s research program on early twentieth century mathematics and logic. Careers were staked on it. Entire fields sprang up around it. It was perhaps the unifying focus of mathematics at the time.

The Incompleteness of Arithmetic

All this changed in 1931.

Kurt Gödel, an Austrian logician – just out of graduate school and only 25 years old – published a paper titled “On Formally Undecidable Propositions of ‘Principia Mathematica’ and Related Systems”. In it he solved Hilbert’s second problem, proving what is today known as the Incompleteness of Arithmetic:

The development of mathematics towards greater exactness has, as is well-known, lead to [… a state] such that you can carry out proofs by following a few mechanical rules. The most comprehensive current formal systems are the system of Principia Mathematica on the one hand, the Zermelo-Fraenkelian axiom-system of set theory on the other hand. These two systems are so far developed that you can formalize in them all proof methods that are currently in use in mathematics, i.e. you can reduce these proof methods to a few axioms and deduction rules. Therefore, the conclusion seems plausible that these deduction rules are sufficient to decide all mathematical questions expressible in those systems. We will show that this is not true, and that there are even relatively easy problems in the theory of ordinary whole numbers that cannot be decided from the axioms. This is not due to the nature of these systems. (“On Formally Undecideable Propositions”, Introduction)

In its most general form, Gödel proved the following:

There is no finite, consistent set of axioms [i.e. rules] from which every truth of arithmetic can be inferred.

In other words: arithmetic is not mere symbol manipulation – it is not pure syntax without a semantics. There is no way to avoid the inconsistency/paradox that Frege’s system was shown to succumb to. Any set of rules, no matter how large or pristine, will either be paradoxical or will fail to prove some part of arithmetic. This is not because arithmetic is somehow inherently paradoxical. It’s just that it’s impossible to reduce arithmetic to symbol manipulation. It’s something more than that. Frege’s program – the animating principle behind nearly 75 years of research in mathematics – was finally dead.

Legend has it that in the fall of 1930, shortly after Gödel had presented his proof for the first time, the celebrated mathematician John Von Neumann was teaching a class on the foundations of mathematics. When Von Neumann learned of Godel’s result, he walked into his class and said “Some young person down in Vienna has just shown that everything we’ve been trying to do for the last 30 years can’t be done. I’m going to present the proof in this course, and then this course is over.” Von Neumann went on to say that:

Kurt Gödel’s achievement in modern logic is singular and monumental – indeed it is more than a monument, it is a landmark which will remain visible far in space and time. … The subject of logic has certainly completely changed its nature and possibilities with Gödel’s achievement.

If it was hard to overstate the importance of Frege’s work to the history of logic and mathematics, it’s perhaps impossible to do so for Gödel’s.

Mere Symbol Manipulation

Gödel’s discovery, despite all of the work that it swept away, led logicians and mathematicians to focus on an important, new question:

What is “mere symbol manipulation”?

If arithmetic is not just symbol manipulation, then what is? Can this notion be characterized precisely? Gödel had already developed the rudiments of such a characterization in order to construct his famous proof. But it was left to others to flesh out the details.

Much of the history at this point is well known. A young Alan Turing, on break before beginning graduate school in 1936, was looking for something to do. So he penned “On Computable Numbers”, in which he gave a precise definition of what he called “automatic machines”. He then sent the paper to Alonzo Church – the inventor of the lambda calculus, and Turing’s future dissertation director – thinking Church might find it interesting. Church immediately saw the significance of what had been done. To his credit, Church went out of his way to make sure Turing got acknowledged for his discovery, despite the fact that Church had already published a formally equivalent result months earlier. He wrote a very generous review of Turing’s paper in The Journal of Symbolic Logic in the spring of 1937, in which he coined the term “Turing Machines”:

[Turing] proposes as a criterion that an infinite sequence of digits 0 and 1 [i.e. a binary string] be “computable” that it shall be possible to devise a computing machine [. . .] which will write down the sequence [. . .] if allowed to run for a sufficiently long time. [Such a machine] can be regarded as a [. . .] Turing machine. (Journal of Symbolic Logic, vol. 2, 1937, p49)

Turing’s fame was thus cemented in history. Church’s Thesis, as it came to be known, was that:

Computation (i.e. mere symbol manipulation) is what a Turing Machine does

At long last, computation theory was born.

Conclusion

That, then, is the connection between logic and computation theory.

Anyone who studies modern logic (A.K.A. “mathematical”, “formal”, or “symbolic” logic) studies the topics discussed above. He learns the actual details of the proofs: their limitations, historical improvements, and how to construct them himself. He learns how to prove theorems within different axiom systems. He studies the meta-properties of those systems – are they complete, compact? He learns different methods (read: algorithms) for checking the validity of inferences, e.g. natural deduction, trees, truth tables. He proves theorems about the effectiveness of these methods/algorithms. And so on.

At it’s heart, anyone who studies logic is doing one thing: he is using non-natural, syntactically and semantically exact languages as tools to solve problems. This is identical to what a software developer does, albeit with languages interpreted by machines.

For these reasons, then, studying logic is actually great preparation for working with computers and learning computer languages.